Kenney Barnard, 75, center, and farm worker Michael Mazejak watch a machine siphon wheat seed out of one of Barnard’s silos. He’s selling this seed to clear the silo to store his harvest of soybeans. Low prices for soybeans this year followed the Trump Administration's tariff war with China.

Kenney Barnard, left, and farm worker Rocky Magness, discuss the farm’s harvest of soybeans this year. While not a bumper crop, this year’s harvest turned out to be pretty decent Barnard said. The question remains as to whether the crop will be profitable.

Rocky Magness, one of Barnard’s farm workers, steers the farm's combine through fields of soy beans in early November. Barnard purchased this combine in 2024.

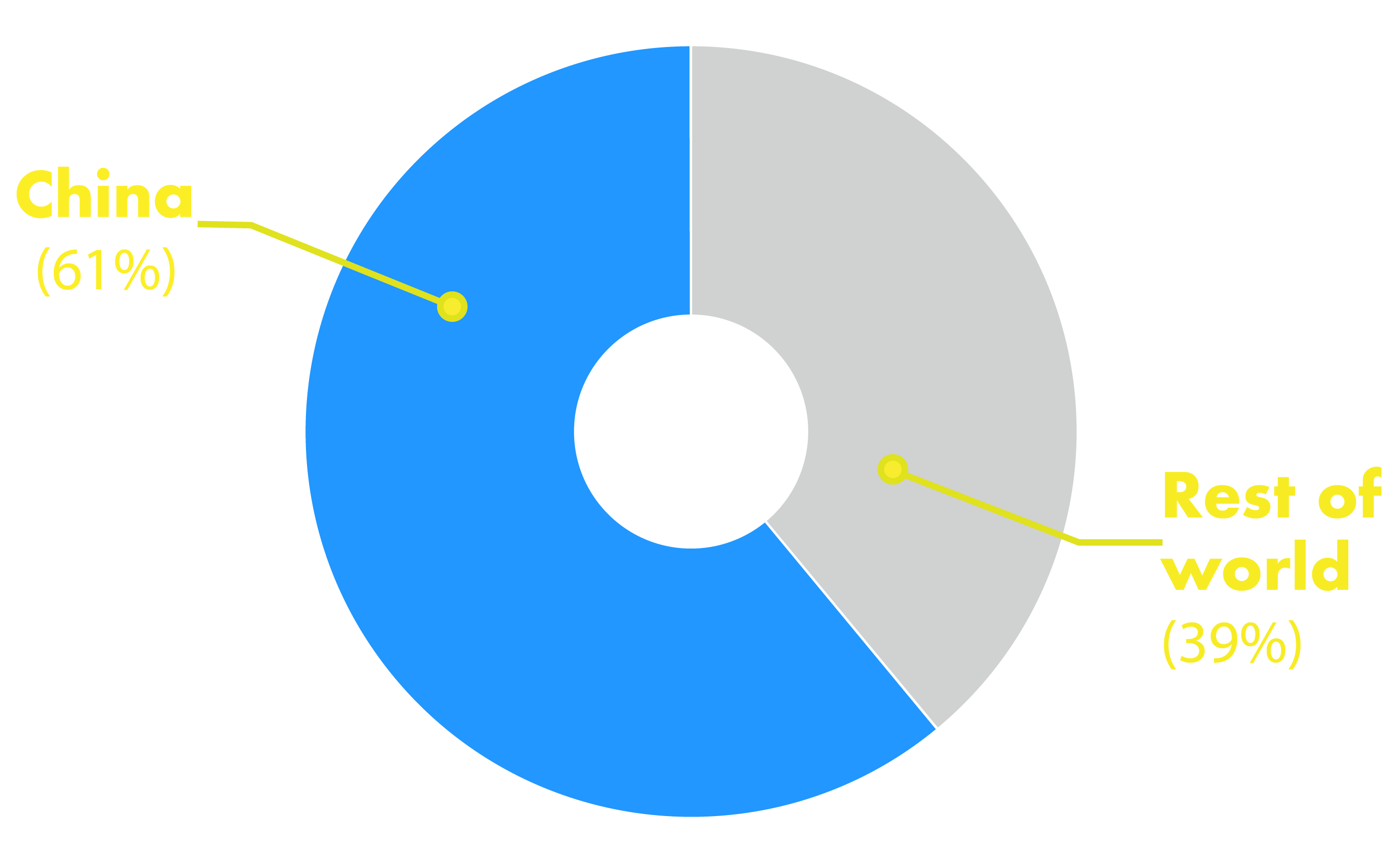

China imports nearly 61% of the world’s production of soybeans, according to the American Soybean Association.

Virginia’s top agricultural and forestry exports in 2023 were soybeans, valued at over $1.4 billion – more than half to China, according to the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. The farming and forestry sectors make up about 9% of the Commonwealth’s GDP, contributing more than $82 billion to the economy annually, according to the Virginia Farm Bureau’s estimates.

Barnard doesn’t shy from sharing his legacy as a descendant of the Confederacy. He continues to support President Trump despite the financial impacts Trump’s policies have had on his business.

Political signs for a Republican candidate are stacked against one of Barnard’s outbuildings.

Barnard sprays an herbicide in early November to kill off weeds before planting winter wheat on one of his many fields.

Dust and chaff swirl around Barnard as he empties one of his six silos to make way for his soybean harvest. He hopes the trade dispute between the U.S. and China is fixed soon so he can sell this crop. The revenue will allow him to plan for the 2026 growing season.

Harvesting and processing tobacco is labor-intensive and largely done by hand. Barnard has relied on the H-2A visa program since the visa program began nearly 40 years ago for workers to grow and harvest 14 acres of the cash crop. Despite the heat on a blazing August morning, Barnard’s migrant laborers cover their faces to shield their identities.

Barnard shares a few words in Spanish with long-time field worker, Martin, right. Many foreign migrants fear immigration raids, and Martin chose not to give his last name despite being an H-2A visa holder. Martin has worked on the farm and led a small crew of migrants for almost 40 years.

In November, Martin and his family strip the dried tobacco leaves, sort them by type and quality, and box them up. Marin usually arrives in early April to prepare for the planting. He stays until the last box is filled.

Barnard peers out from one of his empty silos as the harvest season comes to an end. He’s spent more than 50 years digging in the fertile James River bottomland, harvesting everything from sweet potatoes to flue tobacco and raising all kinds of farm animals. He wonders what the next season will be like.

Martin and his family of seasonal laborers have returned home to Mexico. Over the last 40 years, Martin has spent more time in the U.S. working at Hoot Owl Hollow Farm than he has living in his home country. Changing U.S. immigration and work policies – potentially lowering wages and workforce safety measures – raises uncertainty about whether Martin and his family will return to the farm. (Top photo: Martin and a crew of five workers lived for seven months in this trailer near one of the barns. Worn boots left behind in a cubby by the door to the trailer. Bottom photo: A small suitcase full of dirty clothes and a guitar sits in one of the rooms in the trailer.)